- Home

- Richard Powers

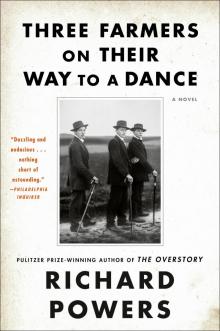

Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance Page 2

Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance Read online

Page 2

The photo caption touched off a memory: Three farmers on their way to a dance, 1914. The date sufficed to show they were not going to their expected dance. I was not going to my expected dance. We would all be taken blindfolded into a field somewhere in this tortured century and made to dance until we’d had enough. Dance until we dropped.

Chapter Two

Westerwald Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, 1914

And somewhere from the dim ages of history the truth dawned upon Europe that the morrow would obliterate the plans of today.

—Jaroslav Hašek, The Good Soldier Švejk

Three men walk down a muddy road at late afternoon, two obviously young, one an indeterminate age. They walk leisurely. One sings:

—Carrots and onions and celery and potatoes. Such thin fare! If my mother had served up a little meat more often, I might never have left home.

He sings in German, but with a Rhenish or even a foreign accent. He is the taller of the two young-looking figures. Both wear matching black suits of a heavy material that scuds up in creases about the elbows, even when the boys straighten their arms. The singer’s hat is taller, more ostentatious, worn more jauntily than the other’s. But this does not destroy the paired impression the two give. The bone running from the eye ridge down into the nose has the identical arch in both faces. They may be brothers. All three carry canes; the singer waves his in a simple, monotonous sweep, conducting his own performance. Carrots and onions. Carrots and onions. It is the first of May in the Rhineland Province of Prussia, 1914.

Their way is a pressed-dirt cow-and-cart trail through stark farmland that tapers, at a few hundred meters’ distance, into a gentle roll. Earlier, a spring shower turned the crushed gravel and dirt mixture of the road into a muddy silt, no good for walking. Pools of water stand where horses’ hooves have torn up the center of the road. The three keep to one edge or the other, where the relative safety of high ground above the packed-down wheel ruts protects their shoes. The singer wears long, flattened, gradually pointing shoes that exaggerate his dandyism. This fine, city-crafted style—the height of fashion this month—will be scorned very shortly and called “dreadnoughts,” after the new battleships. Those of his double are sterner, more sober. The third figure, who wanders absently off the road or into the mud more frequently than the prettier two, wears shoes that, with the largest degree of flattery short of lying, could be called well kept up.

The third loiters behind the others in a fit of abstraction. He runs an experiment on how loosely he can hold a cigarette between his lips. It drops to the ground several times before he can perfect just the proper angle of droop. His shoulders hunch forward in his brown suit, of a lighter material than the others’ but still fit for special occasions. The third one walks a while carrying his arms stiffly at his side. He stops, examines and rearranges his posture, then takes off again, arms flying. He undergoes this stop-and-change every so often, tilting his head each time to observe the effect. His cane serves sometimes as a weapon, sometimes as a prop, sometimes as excess and troublesome baggage. When he looks, for a change, at his friends up in the road ahead, a glance brought on by the sudden halt of song and bickering, he notices that the singer is walking backward in an exaggerated cakewalk, aping him. The lagging figure retaliates with a rude gesture of his own, and the two now obviously young men grin at each other in disarmament.

Faintly over the newly planted fields comes the odor of the last five years’ compost and fresh manure. With this smell, equally faint, comes the sound of an orchestra. Only a stray note or phrase ripped out of context can be heard, the way a letter from a loved one, lying folded for many years, shows only spectral, illegible marks and a dissociated “I hope you are . . .”

The short one of the matched pair speaks:

—Peter, Hubert: listen. Hear that? Brass bands. I knew it would be brass bands again this year. These people, they’re very good people at heart but they have villagers’ imaginations. Never traveled out of the Westerwald, you understand? I’m sorry I’ve made the two of you come so far for a brass band.

He uses a surprising number of words for one whose walk and dress are so succinct. Until the speech, he had kept silent except to return the harpings of his twin. This burst of words carries the demure figure through his bouts of intervening silence.

His match, the singer, Peter, looks for the music but cannot find it. The rear figure, Hubert, still posturing with cigarette, scowls in impatience. But Peter looks curious, amused.

—Oh Adolphe . . .

He calls to his circumspect lookalike, giving the name a playful, effeminate sing-song, a long “e” on the final syllable.

— . . . that’s not a brass band, you scoundrel. That’s a full orchestra with violins. Oh, I’ve got it, Adolphe. You’re not taking us to the charming town of Luden’s May Fair, quaint as such a spectacle must be. You dog-darling. You’re walking your newfound brothers all the way to . . . Vienna!

Peter explodes on the name of the city and pounces, kissing Adolphe sloppily and repeatedly, grabbing and swaying him about in a waltzer’s grip. The smaller boy pushes off the prankster with Teutonic severity, disbursing, briefly, a thesaurus’s listing for “insane.” He straightens his ruffled clothes, adjusts his tie and starched collar. His eyes dart to the joker, now doubled in laughter, and, straightening his hat after the attack, he attempts to imitate the rakish angle of the other’s.

Hubert, still lagging, gets off a good cackle at the brawl, uncontrolled and childish. He speaks with all the control of a bad tragedian trying to deepen his voice.

—We’re not going to no dance or no Vienna. We’re going to May First Soviet.

He says this as an American child of the same era might say, “We’ve got to go kill Jesse James.” The others work at paying him no attention.

—It’s not So-veet, Hubert. It’s So-veet. And say the So-veet, not just So-veet, or people will think you’re talking about a place.

Hubert only grins feebly, and hangs his cigarette steeper from his lips. Still ruffled by the surprise Viennese attack, Adolphe smoothes his suit again, and checks for his billfold in his inside vest pocket. During this entire journey, he has not let ten minutes go by without checking for this same billfold. And there is no one in all of Germany clever enough to sneak up unnoticed through these thousand acres of flat absence to filch his billfold. Still he checks the place of value every few minutes, instinctively, to prove its firm reality.

Peter resumes leading the caravan, moving ahead briskly. He sees a lost Westphalian sparrow hopping in the fields just off the road, trying to get at the April seed in the furrows. The dandy bobs his head in a grotesque parody of pecking, resembling for a moment those frightened children who believe that neck exercises can prevent the horrors of double chins and goiters. Bored, he starts to sing again:

—I might never have left home. Leave home. Leave ho-ho-hoo ho-ho-home.

Then, by association, he starts a new tune:

—How long you have been away from me. Come home, come home, come home.

This second song is livelier than the first, so Peter begins automatically to walk a shade faster. The new tempo soon carries him a few hundred paces ahead of his companions. When he realizes this, he turns on the other fellows and folds his arms. They draw closer, and he shouts:

—Orchestra, Adolphe.

—Brass band, Peter.

They are still more than a mile from their destination, the music’s source. The music carries that far because of the dead stillness in the spring, 1914, air. Sound travels at about 1089 feet per second at freezing, and increases about 1.11 feet per second for each degree Fahrenheit rise in temperature. This crisp May Day is a perfect 68 degrees, so the speed of sound today is around 1129 feet per second. In five seconds, the music—whether it is Bavarian Beer Hall or Viennese Woods—travels 5645 feet, the little over a mile that the three boys are from the site of the May Fair. Five seconds at eighty-five quarter notes a minute means the

waltz they hear is already two measures in the past.

The few notes that do make it this far are long over by the time they make themselves known. Modulation replaces modulation; in two measures’ time the song the boys hear is no longer the song being made. The boys have only outdated music with which to create a belated present. The stars on a clear winter’s night have perhaps novaed a thousand years back, but persist as an undeniable current event. The realities of the past become true only when they intersect the present. Then, only, do they become present, known, regardless of what has happened to them since. Only when grief sets in—grief, like sound, that varies with the temperature of the air—does the past in fact die.

Peter loses his lead to the more businesslike Adolphe. He lags, lost in a reverie, pronouncing out loud the name “Franz Joseph.” He says the name again and again, in as many different ways as he can dream up. One permutation draws the “z” sound out to freakish proportions, then slides it into the “yo” beginning the second word. Another variant imitates the clipped sounds of a Prussian accent—“Frans Chosip”—a dialect that rings false in Peter’s mouth. He speaks, chants, and sings the words until they assume a foreign, deranged quality. When Franz Joseph refuses to respond to any of the entreaties, Peter grows bored. After a few minutes, he resumes his animated, teasing voice, giving it the singsong quality of rhyme that accompanies a game of hide-and-seek.

—Adolphe. A-dol-phee. Maybe, Adolphe, Alicia will . . . A-lee-sha is going to be at the May Fair, Adolphe. And maybe she will want . . . you know, Adolphe.

Adolphe stiffens, reddens, and checks his inside vest pocket.

—Shut up, you would-be brother of mine, or you’ll get this cane but good. I swear it.

It is a perfect, unwitting imitation of von Moltke, the old Franco-Prussian War general. Peter pays him no attention.

—Oh Hubert. Huu-bee. Huu-uu.

He pronounces the word to pun with the Dutch word for “how.” It now becomes obvious that Peter himself is Dutch.

—Maybe some girly who doesn’t know any better will give you your first little nip-and-tuck at the May Fair, Hubert.

Hubert’s face contains no quality of age. It is a clay mask that conforms to the thought of the moment or any preconception of the observer. He removes his worn-down felt hat and passes his hand over the creases in his forehead, creases that seem deep enough to be the product of sixty years or more of garden pain.

—Women like So-veets the best. So-veets have the biggest stalks.

—Don’t say stalk, Hubert. People will think you’re just a child. Say pole. Then people will know you really have a big one.

The boys push each other and laugh. They tell one another exactly what they will do to which girls if they so much as dare show up at the dance.

While wrestling in sport in this way, the boys call one another “brother” in a way that real brothers, growing up together, never would. A cart appears, heading toward the enclave of woods that harbors the music coming from the fair. The boys break off scuffling and try to make themselves look presentable. Middle-class farmers in the cart greet Adolphe familiarly as they pass, but the cart does not stop. Peter grimaces at an imaginary spot of mud thrown onto his suit by the horse’s hooves.

—Verdomme! What do these crazy peasants think they’re doing, hey, Adolphe? Reckless drivers.

Adolphe and Hubert laugh as Peter brandishes a fist and pantomimes a fantasy-revenge on the distant cart.

—People in this valley are still in the last century, Adolphe. Everybody moves so slow they’re all going to be asleep before they get to the May Fair. All sleeping; Frederick Barbarossa, asleep in the Kyffhäuser, his long red beard growing for centuries. But he’ll wake up and lead Chermanee to greatness, hum, ‘Dolphe?

Adolphe makes no answer. Recovering from the interruption of the cart, he heads down the road again. He straightens his hat back to its former, sober angle.

—Adolphe? Are you sleeping, Adolphe? What this sleepy valley needs are a few big Dutch automobiles. Speed, hum, ‘Dolphe? Buy me an auto, A-dol-phee? We had an auto in Holland.

—You lie, brother.

—No, honest, brother. We did. Tell him, Huub. Hu-ub, tell the kind man how everybody in Holland has an auto.

—Well, being Flemish, and a So-veet, I can’t say.

—Oh pooh. You’re about as Flemish as that cow over there. Yaaa, yourself, you big bovine.

Adolphe returns to the others, and to good spirits. He asks:

—Say, what are you, anyway, Hubert? I mean, what nationality?

—I told you, I’m . . .

—Don’t listen to him, Adolphe. He’ll tell you stories all day. He’s worse than a Prussian when it comes to lying. Truth is, a girl friend of Mama’s—cute little ham pattie too, but pushing the middle years now—got knocked up and probably got a telegraph from the womb about the trouble this one would make. She was too busy to care for him, so my father—that is, our father, Adolphe—was big enough to make a place for him in our home.

—Shut up, you. Your pants are open and your intelligence is showing.

—Aw, sniffle in your hanky, orphan.

—Quiet, Peter, and take the log out of your own eye. After all, you’re both living on my mother’s generosity now.

Adolphe’s eyes shine with a triumph that had not come into them until now. The three continue fairward in a renewed silence. Westerwald Rhineland consists of deceptive distances that swallow up and separate the intimate, populated enclosures. Not two hours by cart from Cologne, the region the boys travel nevertheless conceals certain roads that threaten to collapse, just beyond the next seductive rill, into total isolation. The landscape varies from violent, wooded ravines to the boredom of unmitigated open spaces. Just outside the warmth and well-lit hilarity of evening villages lie bogs of solitude. Activity on the road and in the air falls to nothing as the boys draw near the hidden May dance.

Something breaks the spell of silence. A man pedals a bicycle along the dirt track from the direction of Adolphe’s mother’s farm, a farm lying on a clean bevel in front of Cologne, as if threaded on the great spires of the cathedral there. He balances a rucksack full of gear on the front bicycle fender. The three watch curiously as the man hollas and stops, with some difficulty, nearby. He is bearded, perhaps thirty, and wears knickers, gaiters, and a wide-brimmed hat. With the nonchalance of one asking for directions, he calls out:

—You’re wearing your Sunday clothes?

To rural reserve, the boys add the guarded manner saved for the very odd.

—Yes . . . that is . . . there is a dance.

—Of course there is a dance, my young man. Germany has held May festivals for thousands of years. Goes back to the Romans—wine bashes, the spring goddess, Flora, that sort of noise. Now I’ll wager you young fellows didn’t know you were headed to a heathen ritual, heh?

The boys hang spellbound. They cannot figure out how to respond to this strange-talking older man decked in bohemian hat and gaiters. Hubert is the unlikely ambassador for their faction. He takes a chance:

—Are you So-veet?

The cyclist, beginning to unpack his rucksack, curls his upper lip in a sneer of amusement and distaste.

—Social Democrat.

Hubert looks inquiringly at his stepbrother Peter, who mumbles, uncharacteristically softly, that the two are similar, so he thinks—roughly equivalent. Hubert is ecstatic.

—See! I told you that the rich folk can become So-veet too.

The man unpacks photographic prints and plates, which he begins laying out by the side of the road. Adolphe warns him that the way is muddy, but the man pays no attention. Addressing Hubert, the man adds:

—So we’re political, are we? You wish to point out to me that the left has made May first some sort of workers’ demonstration day, is that it? Well, they’re still relative newcomers compared to the Romans and their Flora. Still, that’s fine. Make some noise in the world is what I say. Just don’t fall a

foul of the laws. But why talk about governments and all on a fine evening like this one? Here. Come here and have a look at these.

Despite their reservations, the boys examine the photographic work he has spread out by the side of the wheel track. Adolphe gives a shout of recognition on seeing the image of two landed farmers who work several hundred acres near his mother’s.

—Ha! Look at Herr Jacob all puffed up in his evening dress. Isn’t he just the important man in his photograph?

Then, embarrassed at his sudden profusion, perhaps thinking that he has just unknowingly wounded the pride of this strange man, he lapses into his customary reserve. But the man slaps his hands together, delighted with Adolphe’s response.

—Exactly! See how he has stopped being the Herr Jacob that you talk planting with and has become, in front of the lens, somebody else, something more serious. He has stopped being just an individual with a certain year of birth, a certain year of death—God preserve him, you understand—and, for the sake of the unseen audience, has joined himself to the stream of the universal, the type of the well-to-do working man. The idea of Herr Jacob, if you will.

Now it is the cyclist’s turn to be embarrassed at his explosion. He shrugs, then turns back to his unpacking. He draws a stand, some unexposed plates, and a wooden box camera out of his sack. Peter, poking about, begins to come back tentatively into his own.

—Oh now I see, Mr. Philosopher. You’d like to sell us some pictures here on the grounds that they show . . . whatever it is you said. The Ideal.

—Peter! What a suggestion.

—Not exactly, young fellow, but I knew you would be a shrewd one. Your jawline proves it most definitively.

The Overstory

The Overstory Bewilderment

Bewilderment Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance

Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance Operation Wandering Soul

Operation Wandering Soul Prisoner's Dilemma

Prisoner's Dilemma The Gold Bug Variations

The Gold Bug Variations Generosity: An Enhancement

Generosity: An Enhancement The Echo Maker

The Echo Maker Orfeo

Orfeo The Time of Our Singing

The Time of Our Singing PLOWING THE DARK

PLOWING THE DARK Generosity

Generosity Gain

Gain