- Home

- Richard Powers

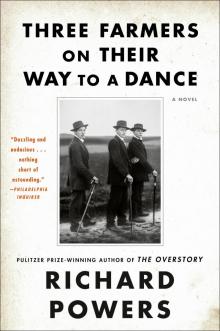

Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance Page 3

Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance Read online

Page 3

Peter puts his hands to his face, suspiciously. Meanwhile, Hubert’s face, which previously, hanging cigarettes and practicing revolution, might have passed for sixty, has in his childlike delight over the photos slipped several decades back to its actual mid-teens.

—Look! My buddies, look at this. Maastricht. I’ve been there. I live there. I mean Peter and I used to live there, huh, Peter? The new tool factory. When were you over there, old man?

—Sad to say, Mr. Soviet, but that is a tool factory in the Ruhr. So many of these are springing up these days that it grows increasingly difficult to tell one from the other. Yet it delights me to no end that you should mistake this one for another in—shall I say—your hometown?

—The revolutionary is a citizen of all countries at once.

—What he means, sir, is that he now lives with me in my mother’s house—over that rise there; we’re mostly turnips this year—and that he’s in the process of becoming a naturalized German.

Peter, caught running his finger over the edge of the wooden camera box, responds with all the flippancy of guilt.

—I come with the package. Two-for-one relatives. What does this instrument perform?

—That, friend, is my outdoor portraiture camera.

—Outdoor . . . ? Now there’s a rich one. I’m good with machines, you know. Not a child. I understand the science of these things. Portraits, if they are to be good ones, need to be done in the studio. Something about strong sunlight blackening or blurring the film. Or like that. Am I right, opa? You are trying to sell us something. Are you French?

—On the contrary, my young jawbone. All the images you see here were made with my outdoor camera.

—You ride a bicycle instead of an auto, and you tell lies for a living. I cannot think of a worse combination.

Adolphe is shocked at his double’s accusation, and apologizes by proxy. The photographer invites Peter to look closely at the images and notice the surroundings: here, the Luden row houses, the ridge of woods across from the Ainsbach fields, or the expanse of Neanderthal valley behind a study of two shepherd children with facial defects. Peter denies the proof.

—I tell you, you magician, I’ve seen all these tricks before. Sure, these were done with cameras. But indoors, in front of backdrops painted to resemble these parts. Very cleverly painted, too, I might add. The illusion of the natural is very convincing.

Portrait photographers at this time always double as oil landscapists. While their backdrops are seldom convincing enough to pass for nature, they can make nature pass for a backdrop.

—The effect would be very artistic, very artificial—almost perfect—if you could keep your subjects from dropping pose at the last minute. Or did you sell the good ones and think you could pass off the remainders on know-no-betters?

The bicyclist continues to look from one younger face to the other, with all the attention and dispassion of a botanist engaged in species identification and nomenclature.

—I can see that the only way I’m going to convince you of the reality of outdoor portraiture is to do one of the three of you. Here, now. The three of you on this road, as I saw you when I rode up.

—See? I knew you were trying to sell us something.

—No, this one will be for science’s sake only, and for the archives: a personal record of the conversation we shared today.

His disclaimer collides with the flattered look that had come across Adolphe’s face. Adolphe liked being selected as good photographic material, and is sorry Peter has spoiled it. He tries to appease the photographer.

—But if . . . supposing we . . . ?

—But if any of you wish to meet me at this same spot next Sunday and look at the results, then we can talk terms if you wish.

Peter takes charge of the boys, attempting to marshal them into a pose that will reflect the sheer heroism of being young. He argues with the photographer, who says he does not want a pose but a natural grouping: the same arrangement they were in—walking along toward Luden—when he interrupted them. Peter demands to know where the craft is in that. The photographer threatens to pack up his bicycle and leave unless the boys behave. Anxiously, Adolphe warns that the sun is going lower and that they had best shoot the picture now or lose the chance forever. And also that they had better hurry on soon to the fair or risk losing the better part of that as well. Peter teases Adolphe that Alicia has no chance at the May Queen because he, Adolphe, by far the prettiest in the Rhineland if not the empire, will sweep the balloting and become the first-ever May King.

The first plate is spoiled because Hubert drops the cigarette out of his mouth and bends down to pick it up just as the photographer opens the lens. The second has got to do because he has no more plates and cannot make his customary backup image.

As the man collects his photos and packs up his gear, Hubert asks him if he belongs to a trade union. The photographer says he scrupulously avoids organizations and advises the boys to do the same. The talk drifts easily from the weather to planting conditions and on to politics, with the photographer deploring the recent Zabern Incident, in which an army officer exploited and humiliated Alsatians. In an unconvincing imitation of someone much older than he, Adolphe warns the photographer not to talk disrespectfully about the Kaiser. The photographer asks Adolphe:

—What do you think the Kaiser had in mind by raising the army to eight hundred thousand men?

Adolphe, again sounding as if he has just recently heard his father say the same thing, replies that he is sick and tired of alarmist talk about war. Such talk shows a selfishness of nature, a weakness of will, and a clamoring for sensationalism. Daily routine is enough, and people shouldn’t go about talking war to liven things up. And besides, military service is an honor.

Three men, only one of them native to the area, are photographed as if they are walking to a not-quite fair. One lags a little behind, cane at a rakish angle, undisciplined hair curling out from under a beaten-up hat. His lip shows the first sign of down. His jaw seems to contain an extra joint just above the chin. Despite ill-behaved ears and a nose that will be too fleshy in old age, he is redeemed from ugliness by eyebrows that recurve into grace. He hangs a cigarette from full, Flemish lips. His dark eyes carry the accumulation of several decades’ pain.

In front of him, a brighter-looking man turns three quarters in a more arrogant attitude toward the camera. His too-long nose seems even more equine in that the nostrils can be seen from head on. Eyes and mouth share a concord of irony that cheek fat and a minute chin cleft attempt to undermine. His left hand closes finger to thumb, in a gesture of covert aristocracy.

In the lead, the youngest face, oldest in years, seems in danger of being routed totally by a starched white collar. His pose is a successful imitation of the middle figure, although rigid in a way suggesting autonomy, or attempted autonomy, as if accusing the model of doing the copying. The arch over the eye is pure nineteenth century. The effect is of a young man trying to preserve something not wholly understood.

All three have stopped left foot in front of right, looking out over their right shoulders at an observer present but remarkably unobtrusive. Behind them, empty fields.

Alicia is at the fair. She lost the May crown to the middle Jacob daughter. Nevertheless, the boys fight for a rotation of dances with her. Hubert asks her what she thinks of the Soviet. Peter tries to put his tongue in her ear. Adolphe asks her what she thinks the Kaiser had in mind by raising the army to 800,000 last year.

Chapter Three

Accommodating the Armistice

. . . Opticians’ shops were crowded with amateurs panting for daguerreotype apparatus, and everywhere cameras were trained on buildings. Everyone wanted to record the view from his window. . . .

—Marc Antoine Gaudin, Traité pratique de la photographie, quoted in Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography

Marching: what five minutes before might have passed for a mid-sized Ford sedan badly in need of a tune-up now unmist

akably became marching. Mays listened to the regular stamp of feet hitting the concrete coming from somewhere in the neighborhood of Clarendon. Ascribing direction to the sound at this point, from eight stories up, was largely speculation, interpolation after the facts. And this noise, definitely marching now, left only the faintest of tracks. That Peter bothered with it at all testified to the less than hypnotic hold of the work in front of him on his desk.

Facing Mays across an impenetrable barrier of potted plants, Moseley, Peter’s colleague, continued to seek the lowest level permitted by his office chair, happily cutting, rearranging, and pasting a manuscript in front of him as if the trampling noise could be nothing more serious than a rattling radiator. Thirty years in the Powell Building—a noisy twelve stories of poured concrete—had conditioned Moseley to ignore all aural phenomena aside from the 5:00 all-clear bell.

But neither editor could cultivate ignorance for long. An affected sergeant’s accent called out drill in the street below:

—Hawp, hawp, wan-te-doop, ga-dinkity-dinkity, hawp.

A concerted shuffling following this epileptic outburst signified a change in squad formation. Snare drums fired off in snappy precision. Mays, perhaps because this was the first parade he’d ever heard without seeing, wondered that no one had ever pointed out to him that marching feet do not move metronomically but in a lopsided, trapezoidal one-two, one-two. Armies lurch; the listener does the smoothing out.

Mays’s interest in what was going on outside the office window gradually escalated, starting with disinterested head bobs, so as not to alarm his cellmates. He coughed, fussed with papers, turned slowly toward the lone window. Peter’s precautions were lost on Moseley, on the far side of the plant wall. The senior fellow breathed heavier, in raspy sforzando, but continued shuffling sheaves. The army marching in the street below would have to ambush him in his pretended ignorance.

When the marching grew louder, Peter caught the eyes of Caroline Brink and Doug Delaney, the other half of the technical masthead of Micro Monthly News. The eighth floor of the Powell Building allowed this eye contact by means of the advanced concept of Modular Officing. “Modular” was an interior decorator’s euphemism for obscuring the fact that the walls separating the editors went only halfway to the ceiling. Moseley, for his part, had tried to rectify this modularity—a violation of his constitutional guarantee of oblivion—by lugging in potted plants one at a time on the commuter shuttle, to build an organic barrier.

—Sounds like the Germans got the East Coast in the divvy-up, Captain.

Dougo Delaney had gotten his first laugh in Mrs. Rapp’s 2-B, when, being asked by the teacher how he was going to learn math if he kept asking for the washroom pass, he had responded, “Process of elimination.” He addressed and saluted his superior, Caroline. Brink, ignoring the irony, asked:

—Where’s that coming from?

Mays felt an urge to tell her not to end a sentence in a preposition, but could not decide if “from” was one. He had always been a little too slow for the obligatory, sadistic office patter. To identify the marching, he would have to stand and crane. He declined to lower himself to active observation. Instead, he addressed the potted-plant barrier:

—Aren’t you going to have a look, Mr. Moseley?

—No. They’re a couple blocks away. Can’t see them from here. It’s nothing, anyway.

His denial galvanized the other three. With a look of complicity, they moved from their modules to the window: if Moseley says they’re too many blocks away to see, then they’re here, in plain sight below the window. Mays’s suspicion—that there was something remarkable, worth looking at, outside—received a last ratification in the unswerving wrongness of the wheezy fellow across the way.

—Brink, come hold my legs.

Delaney, supine on the window ledge, resembled a tackled halfback trying to sneak the ball ahead over the first-down mark. Snares, bagpipes, and drillmaster had been driven aside by the typical parade brass. The new sounds dissipated into random, drunken snippets of “Turkey in the Straw,” the Marines’ Hymn, and an obscure version of “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean.” Particles of Americana collided against each other on the eight-floor trip up the side of the Powell Building, a Brownian motion of regimented anarchy.

Mays, too, had gravitated to the window, but could see only Delaney’s graceless posterior there, Caro keeping it in place. He thought to offer his help, but knew she had the better build and stamina for the job of anchorperson. Moseley, claustrophobic, pushed his wire rims higher on his papier-mâché nose and said something about the musicians being two blocks away. Delaney blandly came within a few centimeters of killing himself on his way back inside.

—Gentlepeople of the press, God damn that son-of-a-bitching Mr. Powell. Off the record, of course.

Not content merely to verb a noun, Delaney was moved by the extent of boss Powell’s crime into participling one. Worse than not getting Veterans’ Day off, the staff of Micro Monthly News had not even been told they wouldn’t be getting the holiday. Not reminded that this was anything but a routine workday, they’d been deprived of the vicarious bitterness that is often more gratifying than the holiday itself. Delaney began making up for lost time.

—Veterans’ Day, you lousy proles. Three quarters of Boston must be out there. Party hats, floats, confetti, buxom young women twirling those white rifles . . .

He grabbed Brink and began half-waltzing, half-polkaing her around the office. He accompanied himself by singing, “O Caroline, My Caroline” to the tune of “O Maryland, My Maryland,” a song he evidently assumed fit the occasion by being vaguely patriotic. In fact, the song is highly separatist, encouraging acts of violence against the same soldiers of the Union marching in the street below. Brink made her Managing Editor’s face and attempted to free herself. Moseley, without changing the cadence of his cutting and pasting, pronounced his judgment on the proceedings, coming dangerously close to unlawfully impersonating an Old Testament prophet:

—Adenoids.

His diagnosis, a malapropism for “adrenals,” implied that Delaney was under the dim influence of sex glands that, if humored, would go away as soon as he gave up the bad taste of being twenty-six.

Mays, roused by the prospect of novelty, decided to have his own look at the parade. He did not yet know that there is no better way of spoiling the exotica of the Thousand and One Nights than to visit contemporary Iran. Nor did he yet know how involving, beyond all reasonable expectation, a simple act of eavesdropping can become.

The ledge made him nervous, and he linked his feet on a runner pipe in the absence of the anchoring Caro. Although this limited him to half of Delaney’s extension, he craned out far enough to see that the commotion eight stories down was not a parade but the breakup of one. Delaney had deliberately and maliciously lied: three quarters of Boston were not in attendance, nor were three quarters of Back Bay, Copley Square, or three quarters of those who worked on the immediate block. By the time the remarkably perfunctory parade passed outside the Powell Building, not even three quarters of the marchers were still present.

Delaney, despite Brink’s protests, was still singing in four and dancing in three, with terrifying effect. Seeing Mays prostrate in the window, he broke off.

—Peter, no! Don’t jump. Powell says he’ll agree to the raise.

Mays came back into the room, registering disgust on the roof of his mouth behind his right front teeth. He had gone to the window in hopes of a spectacle, and had come away instead with a vision of dissolution: wandering battalions, batteries of tubas and euphoniums breaking for the curb in relief, infantry out of sync, jaded clarinetists stopping in mid-note, trumpets draining spit from mouthpieces, clowns tearing off their bibulous noses, small-fry politicians beating hasty retreats, whole regiments pouring into waiting buses.

Delaney resumed the vacated window post with a suicidal leap. Mays, seeing him dangle over the edge, sat down on the office floor, overcome by sympathetic verti

go. Caroline joined him. Her hair fallen and temples swollen from the waltzurka, she did not look like a technical editor specializing in integrated-circuit components and the ostensible big chief of the Micro group.

—Great, isn’t it? Veterans’ Day, and we’re working.

She hit into an unassisted triple play. It was by no means great, they were certainly not working, and it was not even Veterans’ Day. That is, it was not November 11, the anniversary of the armistice of the Fourteen Points, commemorating the end of the First World War. The day on which first one and then the other of two young men of draftable age looked out of a window on what one thought of as a parade and the other as a disappointment was October 29, 1984. An act of Congress had created the discrepancy. Some well-meaning legislator, presumably concluding that the day on which the belligerents in the world’s then largest cataclysm had chosen to sit down and end hostilities fell too close to Thanksgiving, succeeded in moving Armistice Day, which had become Veterans’ Day in light of subsequent events, to the fourth Monday in October, a movable feast and legal holiday. Powell broke the law; instead, any employee of Powell Trade Magazine Group could take Good Friday, “as needed.”

Unaware of how history had been rewritten, Mays sat on the floor contemplating Brink’s overbite and considering his professional relation to her. For weeks after signing on with Micro, rather than attack his first assignment (a somewhat dense piece of prose called “New Printed-Circuit Board Adds Reliability to PCM-type Trans Codes”), he had tried to decipher the loose hierarchy of jobs and job titles of the Powell eighth floor.

At the top was Powell himself, an Annapolis grad who made brief appearances to relieve himself of nautical metaphors at the expense of the under-20K set. Each trade magazine in the Powell holdings—such titles as Synthetics World and Modern Brick Journal—had its own sector. Brink headed up the Electronics Sector, being the only one on the masthead with a real knowledge of the material, most other competent people taking the same higher-paying jobs in industry that Mays had fled.

The Overstory

The Overstory Bewilderment

Bewilderment Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance

Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance Operation Wandering Soul

Operation Wandering Soul Prisoner's Dilemma

Prisoner's Dilemma The Gold Bug Variations

The Gold Bug Variations Generosity: An Enhancement

Generosity: An Enhancement The Echo Maker

The Echo Maker Orfeo

Orfeo The Time of Our Singing

The Time of Our Singing PLOWING THE DARK

PLOWING THE DARK Generosity

Generosity Gain

Gain